Jasper Johns I Pop art I Painting I Printmaking

Jasper Johns Bio

Jasper Johns is an American painter, sculptor and printmaker whose work is associated with abstract expressionism, Neo-Dada, and pop art. He is well known for his depictions of the American flag and other US-related topics.

Born: May 15, 1930 (age 89 years), Augusta, Georgia, United StatesPeriods: Abstract expressionism, Neo-Dada, Modern art, Pop artKnown for: Painting, printmaking

Influenced by: Marcel Duchamp, Hart Crane, Tatyana Grosman

Influenced by: Marcel Duchamp, Hart Crane, Tatyana Grosman

Education: Sumter High School, University of South Carolina, Parsons School of Design

Jasper Johns Pop art

Jasper Johns took creating pop art from everyday images to another level, perhaps showing outstanding creativity in using maps, flags and other world iconic imagery and placing them in an artistic context.

Famed for his brushwork and painterly touch, the modern imagery hid a talented artist in the classical sense who chose Abstracr expressionism as is artistic form of choice.

Recently is famous American Flag sold for more than $28 million . The flags and images he created between 1954 and 1959 heralded the start of the pop art movement.

Good friends with all the major pop artists of the era, he quickly became one of the most famous and wealthiest living artists in the world.

Jasper Johns is said to dance along the pop art line between art and reality, with critics praising the way in which the relationship is deliciously blurred. However critics tend to point to the benal content of the art he produced being as uninteresting as the everyday object. Whatever you think, you can not ask for more iconic imagery than Jasper Johns.

In 1990 Johns was awarded the National Medal of Arts. He is represented by the Matthew Marks Gallery in New York City.

Jasper Johns Paintings

Flag (1954-55)

Artwork description & Analysis: This, Johns' first major work, broke from the Abstract Expressionist precedent of non-objective painting with his representation of a recognizable everyday object - the American flag. Johns built the flag from a dynamic surface made up of shreds of newspaper dipped in encaustic - with snippets of text still visible through the wax - rather than oil paint applied to the canvas with a brush. As the molten, pigmented wax cooled, it fixed the scraps of newspaper in visually distinct marks that evoked the gestural brushwork of the Abstract Expressionists of the previous decade. The frozen encaustic embodied Johns' interest in semiotics by quoting the "brushstroke" of the action painters as a symbol for artistic expression, rather than a direct mode of expression, as part of his career-long investigation into "how we see and why we see the way we do."

The symbol of the American flag, to this day, carries a host of connotations and meanings that shift from individual to individual, making it the ideal subject for Johns' initial foray into visually exploring the "things the mind already knows." He intentionally blurred the lines between high art and everyday life with his choice of seemingly mundane subject matter. Johns painted Flag in the context of the McCarthy witch-hunts in Cold War America. Then and now, some viewers will read national pride or freedom in the image, while others only see imperialism or oppression. Johns was one of the first artists to present viewers with the dichotomies embedded in the American flag. Johns referred to his paintings as "facts" and did not provide predetermined interpretations of his work; when critics asked Johns if the work was a painted flag, or a flag painting, he said it was both. As with other Neo-Dada works, the meaning of the artwork is determined by the viewer, not the artist.

Encaustic, oil, and collage on fabric mounted on plywood, three panels - The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Target with Four Faces (1955)

Artwork description & Analysis: In this work, Johns effectively merged painting and sculpture while wittily engaging the viewer with "things which are seen and not looked at." As in Flag, Johns relied upon newspaper and fabric dipped in encaustic to build the intricately textured surface of the painting. However, he also made plaster casts of only the lower half of a female model's face over four successive months, and fixed these out of order in a hinged, wooden box that he attached to the top of the canvas. By incorporating the sculptural elements in the same space as the painting, Johns emphasized the "objecthood" of the painting, as Rauschenberg did in his "combine paintings" of the late 1950s. This merging of mediums reinforced the three-dimensional object-ness of the paintings and was the Neo-Dada response to the recent progression of abstraction away from representation to an ever more reduced imagery that merely reiterated the surface of the canvas.

Beyond the material surface of the work, the concentric circles of the target imply the acts of seeing and taking aim. However, Johns excluded the model's eyes from the plaster faces, and thus thwarted any exchange of gazes between the viewer and the faces in the work. This forced the viewer to examine the interactions between the painted target and the plaster faces. Viewed through the lens of the Cold War era, the seemingly benign images can imply the targeting of the anonymous masses by global political powers as well as by corporate advertising and the mass media. Conversely, contemporary viewers might read the anonymity of the Internet in the work. Every individual's interpretation is shaped by his or her own history and knowledge. As part of his continued exploration of how people see the world around them, Johns intentionally chose the vague symbols of the target and a nondescript human face to solicit multiple, varied readings of this elusive work that straddles two historically distinct mediums.

Encaustic on newspaper and cloth over canvas surmounted by four tinted-plaster faces in wood box with hinged front - The Museum of Modern Art, New York

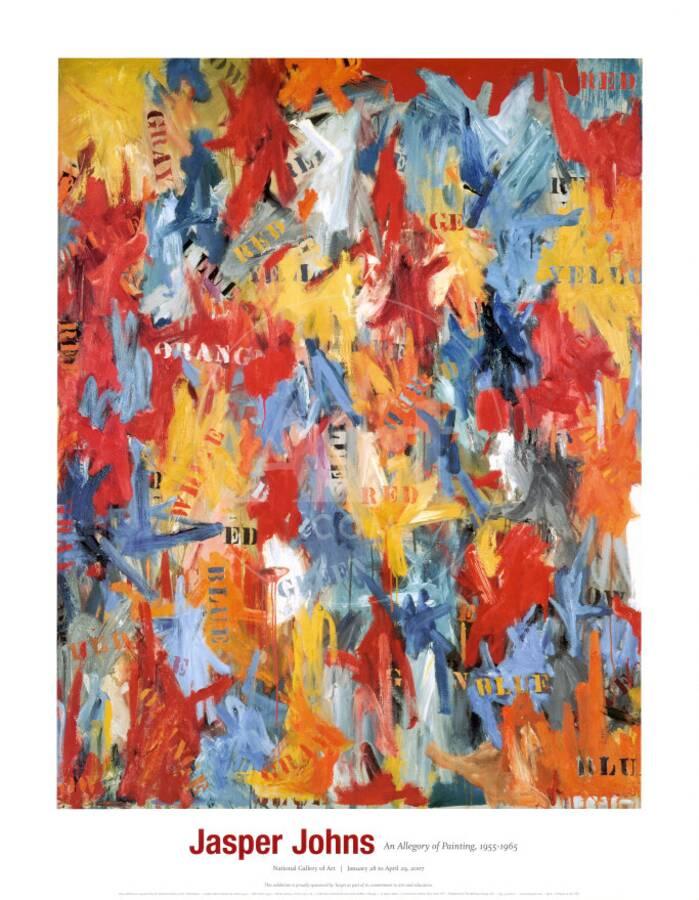

False Start (1959)

Artwork description & Analysis: For this piece, Johns eschewed the nonverbal symbols of his earlier works, instead relying upon the building blocks of language to draw viewers into a dialogue with the painting. The change of subject matter was occasioned by Johns' desire to move beyond his earlier targets and flags. As he noted, "The flags and targets have colors positioned in a predetermined way. I wanted to find a way to apply color so that the color would be determined by some other method." By focusing on colors and the words that represent them, Johns abstracted each, removing the traditional associations that accompanied them. Rather than hand-paint each letter, Johns used a store-bought stencil - a readymade method by which he could create an image without revealing the trace of the artist's hand. He stenciled the words that denote colors on top and underneath the various layers of paint as he worked. Johns transformed the words into objects by rendering most in colors unrelated to those which they verbally represented - "RED" appears painted in bright orange in the center of the canvas. Johns revealed the dissonance between the words and the colors, shifting their function from designation to a mere assembly of symbols, ripe for reconsideration.

Although he shifted media from encaustic to oil, Johns maintained his dialogue with the Abstract Expressionists through a technique he called "brushmarking." Influenced by John Cage's interest in the role of chance, Johns used the gestural technique of applying small sections of paint to the canvas purely according to arbitrary arm movements rather than any preconceived placement for each individual brushstroke. His use of brushmarking resulted in explosive bursts of color, as if in an erupting fireworks display, that highlight or obscure the uncannily hued words scattered across the canvas. The tension between the dynamic colors and the words dispersed among them creates the space for viewers to engage with what they see on a semiotic level. By incorporating language into his visual repertoire, Johns expanded his dialogue with viewers to encompass the function of visual and verbal symbols. His exploration of language stands as a clear precursor to Conceptual art's examination of words and their meanings in the late 1960s.

Oil on canvas - Private collection-Anne and Kenneth Griffin

Jasper Johns printmaking

Printmaking has been integral to the work of preeminent American painter Jasper Johns (born 1930) throughout his career. He approaches each project with a thorough knowledge of the medium, exploiting its intrinsic characteristics—mark-making, replication, reversal, layering, fragmentation, and memory.

| Painted Bronze (ale cans) (1960)Artwork description & Analysis: In this bronze sculpture, Johns intentionally blurs the line between the actual object and its artistic recreation, wherein the handcrafted appearance of the Ballantine Ale cans is only apparent after close inspection. He fashioned the sculpture in response to Abstract Expressionist Willem de Kooning's boast about art dealer Leo Castelli, "you could give [him] two beer cans and he could sell them." Johns accepted the challenge implicit in De Kooning's statement, casting in bronze two cans of his beer of choice, Ballantine Ale, which Leo Castelli promptly sold. The original beer cans were a deep brass-colored metal, which was ideal for casting in bronze to achieve an effective trompe l'oeil effect. However, in contrast to the authentic appearance of the cast cans, he allowed his brushstrokes to remain visible in the painted labels, creating an imperfection visible only upon careful observation. |

Johns cast each can and the base separately and imprinted his thumb in the base as the autographic mark of the artist's hand, ensuring that the work is handmade. Johns cast one can with an open top and painted the Ballantine insignia and the word Florida on its top. The other can is unopened, unmarked, and solidly impenetrable. Some critics read the contrast between the cans as a metaphor for the relationship between Johns and Rauschenberg - an illustration of the differences and the growing space between them. In this reading, the open can serves as a signifier for the gregarious and popular Rauschenberg who began spending much of his time in his Florida studio in 1959, while the closed one stands for Johns and his quiet, impenetrable public facade. Other critics read a narrative of everyday life into the difference between the two cans - that everyone lives their lives between the after, or what has already happened embodied by the opened can, and the before, or what has yet to transpire in the closed can. Despite some clues, like the thumbprint, Johns left the final interpretation of the sculpture open to the viewer's discretion. His foray into representing mass-produced goods within the realm of fine art paved the way for Pop art.Oil on bronze - Museum Ludwig Koln

Comments

Post a Comment